BITCOIN AS

SOUND MONEY

BITCOIN AS

SOUND MONEY

Explore how Bitcoin restores financial integrity with fixed supply, decentralization, and resistance to inflation. This resource breaks down why Bitcoin isn’t just digital currency—it’s the foundation for a more stable, honest monetary future.

"Bitcoin fixes the root of economic instability: money that loses value over time.”

– Saifedean Ammous

"Bitcoin fixes the root of economic instability: money that loses value over time.”

– Saifedean Ammous

Featured

The Bitcoin Standard: A Deep Dive into Saifedean Ammous’s Masterpiece

“Sound money is chosen freely on the market for its salability, not imposed by government decree. It protects value across time, allowing civilization to flourish.” -Saifedean Ammous

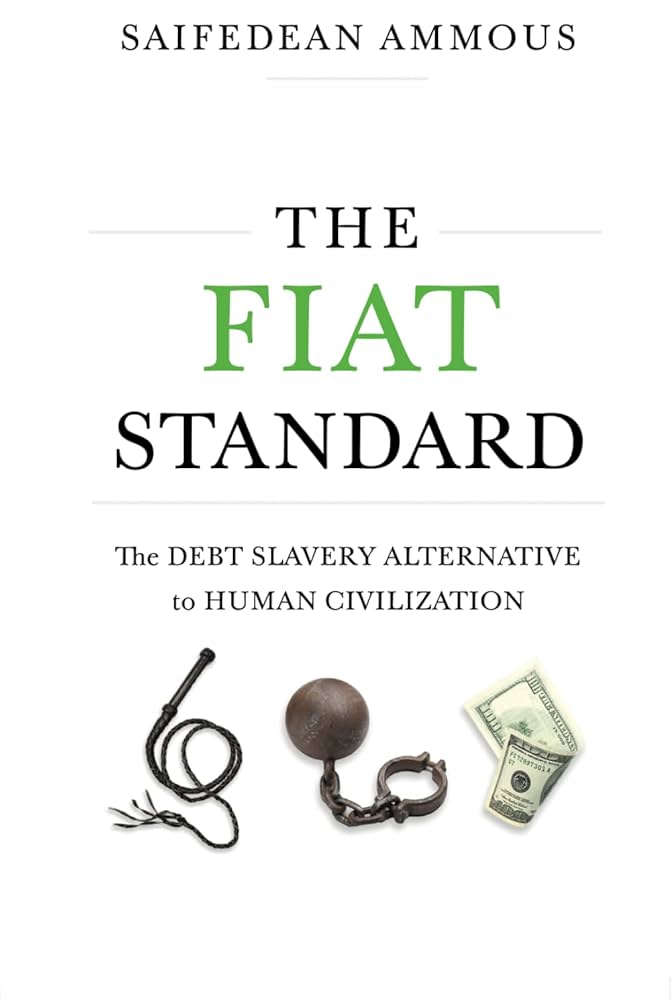

When Saifedean Ammous published The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking in 2018, it quickly became one of the most influential works in Bitcoin literature. Unlike books that frame Bitcoin as a speculative asset or a quirky tech innovation, Ammous approached it through the grand lens of history and economics. He asked: What is money, how has it evolved, and why does Bitcoin matter in this lineage?

The result is not just a book about Bitcoin. It is a sweeping intellectual journey that explains why civilizations thrive on sound money, how fiat money corrodes culture and freedom, and why Bitcoin may represent the rebirth of incorruptible money for the digital age.

At its core, Ammous presents three interlocking arguments:

Money is information, and civilizations only thrive when that information is reliable.

Inflationary fiat money distorts time preference, undermining savings, freedom, and culture.

Bitcoin is the first truly incorruptible form of digital hard money, uniquely suited for the modern world.

This article will take a deep dive into these ideas, expanding on the book’s framework with historical examples, economic insights, and technical detail to give a full picture of Ammous’s work.

Part I: The History of Money

“Throughout history, the choice of money has determined the fate of empires. Civilizations that adopted sound money thrived; those that debased it fell into decay.” -Saifedean Ammous

Money is so woven into the fabric of our daily lives that most people rarely stop to ask what it actually is. We use dollars, swipe cards, tap phones, and check balances in apps, but the concept of “money” itself often goes unquestioned. Saifedean Ammous opens The Bitcoin Standard with a journey into history, showing that money is not a human invention in the way lightbulbs or cars are. Instead, money is a discovery—an emergent social technology refined across millennia.

To understand Bitcoin, Ammous argues, we must first understand how humans have always converged on the best forms of money. That story begins thousands of years ago.

Primitive Monies

The earliest human societies relied on barter: direct exchange of goods and services. A farmer might trade wheat for a neighbor’s livestock, or a fisherman might swap his catch for tools. But barter breaks down quickly as economies grow. What if the farmer needs shoes, but the shoemaker doesn’t want wheat? This is called the “double coincidence of wants” problem: trade requires both parties to want exactly what the other has at the same time.

The solution was money—an intermediate good that everyone accepts, not for its immediate use, but because it can be exchanged later for what they truly want. In different cultures, people adopted what they had available and trusted. In Africa, it was cattle. In the Pacific Islands, it was cowrie shells and massive limestone rai stones. In Native American cultures, beads and wampum served this purpose. In Mesopotamia, grain functioned as a store of value and a unit of account for temple economies.

These forms worked for small communities, but they had flaws. Grain could rot. Shells could be gathered in abundance, inflating supply. Livestock could die or be stolen. Over time, human societies converged on materials with better monetary properties: scarce, durable, divisible, portable, and hard to counterfeit.

The Age of Metals

Metals emerged as superior money because they were scarce in nature, relatively durable, and measurable. Copper, bronze, silver, and gold were adopted across civilizations, not because kings decreed it, but because merchants and ordinary people gravitated toward them. They solved the problems of barter and primitive money by offering reliability and universal acceptance.

Gold, in particular, stood out. It doesn’t tarnish, corrode, or decay. It is rare enough to prevent oversupply but abundant enough to mint into coins. It is divisible into small units and easily recognizable across cultures. For these reasons, gold became the ultimate store of value.

History is full of examples. The Greeks minted silver drachmas that became the dominant trade currency in the Mediterranean. The Romans issued the gold aureus and later the solidus, which circulated across Europe and beyond for centuries. In China, dynasties minted copper coins, but merchants often preferred silver for its scarcity and durability.

By the Middle Ages, gold and silver had become the backbone of global commerce, circulating along trade routes that stretched from Europe to Asia.

The Gold Standard

The 19th century marked the height of sound money in the form of the classical gold standard. Under this system, paper banknotes were directly redeemable for gold. Nations pegged their currencies to a fixed amount of gold, which anchored exchange rates and facilitated booming international trade.

What made the gold standard powerful was its restraint. Governments could not print money freely; if they issued more notes than their gold reserves could back, people would redeem paper for gold and drain the vaults. This discipline forced governments to live within their means and created extraordinary monetary stability.

The result was a century of relative price stability and unprecedented economic growth. The industrial revolution thrived under sound money, and global trade networks expanded with confidence.

War, Inflation, and the End of Gold

Sound money’s Achilles’ heel was political pressure. During World War I, governments suspended gold convertibility to finance military spending with inflation. After the war, nations attempted to restore gold but failed to maintain credibility.

The interwar years saw chaotic currency devaluations, debt crises, and the rise of central banking power. The final nail in the coffin came in 1971, when U.S. President Richard Nixon closed the gold window, ending the Bretton Woods system and severing the dollar’s link to gold. From that point forward, the global monetary system was entirely fiat: money backed by government decree rather than scarcity.

The Age of Fiat

Fiat money marked a sharp departure from thousands of years of monetary evolution. For the first time in history, every major global currency was backed not by gold, silver, or any scarce commodity, but by the authority of governments.

This unleashed new dynamics. Governments could inflate at will, using money printing to fund deficits, wars, and social programs without immediately raising taxes. Central banks emerged as powerful institutions, setting interest rates and managing economic cycles.

But fiat came with costs. Inflation became a permanent feature of modern economies. The dollar lost over 85% of its purchasing power since 1971. Wealth inequality grew as those closest to new money—banks, governments, corporations—benefited first. Financial crises multiplied, from the stagflation of the 1970s to the global crash of 2008.

In Ammous’s telling, fiat is not progress. It is a regression from centuries of sound money discipline to an era of political manipulation and economic instability.

Why History Matters

By tracing this arc, Ammous sets the stage for Bitcoin. He shows that money is not whatever a government says it is. Instead, money evolves through the market, chosen by people for its ability to hold value and facilitate exchange.

From shells and cattle to gold and silver, humanity has always gravitated toward the hardest money available—the one most resistant to debasement. Fiat, then, is an anomaly, a break from tradition driven by political expediency. Bitcoin, Ammous argues, represents a return to this natural process: the adoption of the hardest money available, this time in digital form.

Part 1 Conclusion

The story of money is the story of civilization itself. Every empire rose on sound money and fell when its currency was debased. The Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, and countless others followed this pattern.

The Bitcoin Standard begins by placing Bitcoin in this context. It is not a speculative plaything or a technological curiosity, but the latest chapter in humanity’s quest for incorruptible money. By understanding the past, Ammous argues, we can see why Bitcoin’s future may be world-changing.

Part II: Sound Money vs. Fiat Money

“Unsound money is not just an economic problem—it is a moral one. It destroys savings, rewards debt, and shifts power from individuals to governments.” -Saifedean Ammous

If Part I of The Bitcoin Standard is about how money has evolved, Part II is about what money does. Saifedean Ammous argues that money is not a neutral tool. The quality of money shapes the incentives, values, and trajectory of entire societies. When money is sound, it encourages savings, investment, and long-term planning. When money is unsound—easily inflated or manipulated—it corrodes those same virtues, replacing them with short-term consumption, debt, and instability.

What Makes Money “Sound”?

Sound money has two defining features:

Hard to produce: New units cannot be created easily, which keeps supply limited.

Easy to verify: Holders can quickly confirm authenticity, preventing counterfeiting.

Gold is the classic example. Its scarcity and difficulty of mining made it reliable across centuries. Fiat money, on the other hand, is created at will by governments and central banks. Its supply expands far beyond any natural limit, eroding trust over time.

Sound money provides a stable measuring stick for economic activity. Just as a reliable ruler allows engineers to build precise structures, reliable money allows entrepreneurs, investors, and households to plan for the future. When money itself is unstable, the entire economy is built on shifting sands.

The Austrian School vs. Keynesianism

Ammous grounds his critique in the Austrian School of economics, which emphasizes individual choice, savings, and the importance of time preference (how much people value present consumption over future consumption). Austrians argue that tampering with money distorts these choices, creating booms and busts.

By contrast, Keynesian economics—the dominant school since the 20th century—argues that governments should actively manage demand through monetary and fiscal policy. In recessions, they encourage spending and borrowing to “stimulate” growth. To Austrians like Ammous, this is short-term sugar high at the expense of long-term stability.

The two schools represent fundamentally different views of money:

Keynesians: Money is a policy tool to smooth cycles.

Austrians: Money should be neutral and reliable so people can coordinate freely.

Bitcoin, in Ammous’s telling, firmly belongs in the Austrian tradition.

Inflation: The Hidden Tax

One of Ammous’s sharpest critiques of fiat money is its reliance on inflation. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money over time. A dollar today buys less next year, not because goods inherently rise in price, but because the money supply expands.

Inflation works as a hidden tax. Instead of raising taxes directly, governments create new money to fund spending. Those who receive the money first—banks, corporations, and the state itself—benefit before prices rise. Ordinary savers, wage earners, and retirees feel the pinch later.

This process, called the Cantillon Effect, quietly transfers wealth from the many to the few. It is not a side effect of fiat; it is the mechanism by which it operates.

Case Studies in Fiat Failure

History is littered with examples of fiat’s corrosive effects.

Weimar Germany (1920s): To pay reparations and debts after World War I, Germany printed money uncontrollably. At the peak, prices doubled every few days, and ordinary citizens carried wages home in wheelbarrows. Middle-class savings evaporated, fueling social unrest that contributed to the rise of extremism.

Zimbabwe (2000s): Political corruption and economic collapse led to hyperinflation where the government printed trillion-dollar notes. Savings were obliterated, and people reverted to barter and foreign currencies.

Argentina (1980s to today): Persistent double- and triple-digit inflation has eroded trust in the peso. Citizens often convert wages to dollars immediately, knowing their local currency will lose value rapidly.

Lebanon (2020s): The Lebanese pound collapsed as the banking system imploded. Ordinary people lost access to savings, while elites moved money abroad.

Each case underscores Ammous’s point: fiat is inherently unstable. Even in countries without hyperinflation, steady inflation corrodes savings and encourages speculation. The U.S. dollar, seen as the strongest fiat currency, has lost over 85% of its purchasing power since leaving the gold standard in 1971.

Time Preference and Culture

The Austrian concept of time preference is central to Ammous’s argument. Time preference measures how much people value present goods over future goods.

Low time preference: Willingness to save, defer gratification, and invest in the future.

High time preference: Preference for immediate consumption and debt-fueled spending.

Sound money lowers time preference. If money holds value, saving becomes rational, which funds investment in capital goods, technology, and infrastructure. Families think generationally, and societies build enduring institutions.

Fiat raises time preference. If money loses value every year, saving is irrational. Borrowing and spending become the default. Individuals prioritize short-term consumption over long-term planning. This affects not only personal finance but also cultural output.

Ammous draws stark contrasts: under sound money, civilizations built cathedrals that took centuries to complete. Under fiat, we build disposable strip malls and cookie-cutter housing designed to be replaced in decades. Art, architecture, and even social stability reflect the incentives baked into money.

Fiat and State Power

Another key consequence of fiat is its expansion of government power. Under the gold standard, states had to collect taxes directly to fund wars or welfare. This created accountability: raising taxes risks voter backlash.

Fiat breaks this link. Governments can print money to cover deficits, financing wars, bailouts, and entitlement programs without visible taxation. Citizens still pay, but through inflation rather than explicit tax bills.

This stealth taxation empowers states to undertake policies that would otherwise be impossible. World wars, permanent welfare states, and massive national debts are all features of the fiat era.

Debt and Financialization

Fiat also incentivizes debt over savings. If money loses value over time, borrowing now and repaying later with devalued currency becomes attractive. For governments, corporations, and households alike, debt is rewarded.

This creates what Ammous calls a culture of financialization—where wealth is pursued not through production and savings but through speculation, leverage, and complex financial products. Instead of stable growth, economies swing between bubbles and crashes.

Bitcoin, as a hard asset with fixed supply, runs counter to this trend. It rewards saving and discourages reckless borrowing.

Why Sound Money Matters

Ammous’s point is not just theoretical. Every society that has debased its money has eventually declined. From the Roman Empire diluting its silver denarius to modern nations inflating away their currencies, the pattern is the same: unsound money undermines trust, erodes savings, and weakens civilizations.

Sound money, by contrast, anchors societies. It restrains governments, rewards prudence, and lowers time preference. It encourages building for the future rather than consuming in the present.

Bitcoin, in this framework, is not just another asset. It is a return to sound money in an age of fiat decay.

Part 2 Conclusion

Part II of The Bitcoin Standard makes the book’s most radical claim: that fiat money doesn’t just distort economies—it distorts entire cultures. It raises time preference, fuels debt, expands state power, and corrodes the foundations of civilization.

For Ammous, sound money is not optional. It is the bedrock of free markets, individual responsibility, and cultural flourishing. And in a world dominated by fiat, Bitcoin stands as the only candidate capable of restoring that bedrock.

Part III: Bitcoin as Digital Hard Money

“For the first time, humanity has a form of money that is hard by mathematical design. Bitcoin is the most advanced technology for preserving value across time and space.” -Saifedean Ammous

After tracing the history of money and diagnosing the problems of fiat, Saifedean Ammous shifts to the centerpiece of The Bitcoin Standard: the argument that Bitcoin represents the hardest money humanity has ever known. Unlike gold, which is vulnerable to centralization, and unlike fiat, which is printed without limit, Bitcoin is digitally scarce, mathematically secured, and globally decentralized. It is not just another payment app or speculative asset. It is the first credible form of incorruptible digital money.

Scarcity Enforced by Code

The defining feature of Bitcoin is its fixed supply. There will only ever be 21 million coins. New coins are issued roughly every 10 minutes as “block rewards” for miners who secure the network. Every four years, the reward is cut in half, an event known as the halving. This process will continue until around the year 2140, when the last fraction of a Bitcoin is mined.

No individual, corporation, or government can change this schedule without convincing the majority of the network’s participants to adopt new rules—a near impossibility. This is fundamentally different from gold, where new discoveries or technological breakthroughs in mining can increase supply, and fiat, where central banks expand supply daily.

By removing discretion and replacing it with automated scarcity, Bitcoin sets a new standard: money that is immune to inflation by design.

Decentralization and Trust Minimization

Bitcoin is decentralized in a way no prior money has been. Its ledger, the blockchain, is maintained by thousands of nodes spread across the world. Each node keeps a full copy of the history of transactions, and each verifies new transactions according to consensus rules.

This design eliminates the need for trust in central authorities. With gold, people had to trust banks to store it safely. With fiat, they must trust governments and central banks to restrain themselves. With Bitcoin, no trust is needed—only verification. Anyone can download the software, run a node, and enforce the rules.

This decentralization makes Bitcoin resistant to censorship and seizure. No single government can alter its supply, freeze accounts, or block transactions. In an era where financial surveillance is expanding, Bitcoin provides the first globally accessible alternative.

Proof-of-Work and Energy Security

One of Ammous’s most important defenses of Bitcoin is its proof-of-work system. Miners compete to solve cryptographic puzzles, expending energy in the process. The first to solve adds a block of transactions to the chain and receives the block reward.

Critics often call this “wasteful.” Ammous argues the opposite: it is precisely this energy cost that secures Bitcoin. Just as gold’s scarcity is guaranteed by the physical difficulty of mining, Bitcoin’s scarcity is guaranteed by the energy required to alter its ledger.

To rewrite Bitcoin’s history, an attacker would need to control over 50% of global mining power, spending astronomical amounts of energy. The cost of attacking outweighs the benefit. In this way, proof-of-work turns energy into incorruptible digital property rights.

The Difficulty Adjustment

Perhaps Bitcoin’s most ingenious feature is its difficulty adjustment. Every 2,016 blocks—about two weeks—the network automatically recalibrates mining difficulty so that blocks continue to arrive roughly every 10 minutes, no matter how much computing power is added.

This feedback loop ensures Bitcoin’s stability. Even if mining capacity doubles or halves overnight, the network adjusts. No central planner coordinates this; it is built into the protocol itself.

The difficulty adjustment is what makes Bitcoin’s monetary policy unbreakable. Unlike gold rushes that flood supply or fiat policies that swing with politics, Bitcoin’s issuance schedule continues with machine-like precision.

Settlement Money vs. Transaction Money

One of the criticisms Ammous addresses is that Bitcoin is “too slow” or “too volatile” to serve as money. Transactions take about 10 minutes to confirm, and fees can rise during high demand.

Ammous reframes this by distinguishing between settlement money and transaction money. Gold served as settlement money in the past—banks and nations used it to finalize large transfers—while paper notes, checks, and later digital payments served everyday needs.

Bitcoin functions similarly. Its base layer is designed for secure, irreversible settlement. For everyday payments, second-layer solutions like the Lightning Network handle instant transactions with negligible fees. Bitcoin anchors the system with incorruptible scarcity, while higher layers provide convenience and speed.

This layered model mirrors the history of money, with Bitcoin as the digital gold at the foundation.

Comparisons to Gold, Fiat, and Altcoins

Ammous makes clear that Bitcoin is not just “another cryptocurrency.” Its combination of scarcity, decentralization, and proof-of-work gives it monetary properties unmatched by alternatives.

Gold vs. Bitcoin: Gold is scarce and durable but costly to transport and store. It centralizes in vaults, making it vulnerable to seizure and government control. Bitcoin is weightless, teleportable, and self-custodial, immune to centralization pressures.

Fiat vs. Bitcoin: Fiat is infinitely inflatable, backed only by political promises. Bitcoin is finitely scarce, backed by cryptography and consensus. Fiat rewards debt and punishes savers; Bitcoin rewards saving and punishes reckless borrowing.

Altcoins vs. Bitcoin: Thousands of cryptocurrencies have emerged, but most lack Bitcoin’s decentralized security or fixed monetary policy. Many are controlled by small development teams or subject to changes that undermine scarcity. For Ammous, Bitcoin is the only digital asset that qualifies as hard money.

Resistance to Seizure and Censorship

One of Bitcoin’s most powerful features is its resistance to seizure. Gold can be confiscated, as the U.S. government did in 1933 when it outlawed private gold ownership. Fiat balances can be frozen or debited by banks or governments.

Bitcoin is different. With private keys, individuals can hold their wealth beyond the reach of any authority. Moving millions of dollars in Bitcoin requires nothing more than memorizing a 12-word seed phrase. For people living under authoritarian regimes or in collapsing economies, this is not theoretical—it is life-changing.

A New Foundation for Civilization

Ammous does not argue that Bitcoin is perfect or complete. Its volatility remains high, and its adoption is still in early stages. But he insists that its fundamental qualities—scarcity, decentralization, incorruptibility—make it the soundest money humanity has ever discovered.

If Bitcoin becomes the global monetary standard, it could restore the virtues of low time preference, saving, and long-term planning. Just as the gold standard anchored the industrial revolution, a Bitcoin standard could anchor a new era of innovation and stability.

In Ammous’s framing, Bitcoin is not protest money or speculative money. It is protocol—a neutral monetary layer that civilization can build upon.

Part 3 Conclusion

Part III of The Bitcoin Standard makes Ammous’s boldest claim: that Bitcoin is not just “digital gold,” but a new foundation for global civilization. By enforcing scarcity through code, decentralization, and proof-of-work, it achieves what no money before it has—absolute immunity to debasement.

Critics may dismiss Bitcoin as volatile or impractical, but Ammous challenges them to see the bigger picture. Every prior money emerged through market selection, and Bitcoin is simply the next step. If history favors the hardest money, Bitcoin is poised to become the standard of the digital age.

Conclusion: The Standard for the Digital Age

The Bitcoin Standard is more than an introduction to Bitcoin. It is a sweeping history, a scathing critique of fiat money, and a manifesto for digital sound money.

By framing Bitcoin as the culmination of humanity’s search for incorruptible money, Ammous elevates the conversation beyond speculation and price charts. He forces us to consider: What happens to a world where money cannot be debased?

Whether one agrees with all of Ammous’s arguments or not, his book has already shifted the conversation. Investors, economists, and policymakers alike now grapple with the possibility that Bitcoin may not be a bubble or a fad, but the foundation of a new monetary order.

If fiat corrodes freedom, savings, and civilization, then Bitcoin is not just a financial innovation. It is a civilizational one.

Shout out to BullishBTC.com for helping you cut through the noise and get to the signal on Bitcoin.

Bitcoin: The Perfect Solution to Broken Money

The Stories We Tell About Money

The Bitcoin Standard | Saifedean Ammous

True Cost of Inflation | Michael Saylor and Lex Fridman

Explained: What Is Sound Money?

Escaping the Global Banking Cartel - Bitcoin as an Exit

No More Inflation | Why Everything Gets More Expensive & What We Can Do About It

Hard Money - WTF Happened in 1971?

OUR GOAL

Our goal is to educate others on the value of owning Bitcoin from both a financial and humanitarian perspective.

QUICK LINKS

© 2025, BullishBTC. All rights reserved.